Suspended scaffolds, that is, those elevated platforms hanging by wire ropes, have several key components. The first key component is the wire rope. The second key component is the equipment at the upper end of the wire rope that holds everything in the air. The third key component is the platform and hoist that keeps the occupant in the proper location while hanging from the wire rope up in the air. The fourth key component is the tie back system so if component 2 doesn’t work so well, the operator won’t experience a cataclysmic failure, just a subtle one that suggests that something isn’t quite right with the world. And finally, the fifth key component is the personal safety system the occupant wears in case components 1 through 4 don’t work so well.

It should be reasonably apparent that the wire rope in a suspended scaffold only works if the end at the top of the building remains at the top of the building while it is being used. A sudden loss of the attachment point is not a good thing. Therefore, while all the components of a suspended scaffold are critical to the welfare of the scaffold user, it is my opinion that the rigging at the roof is most critical.

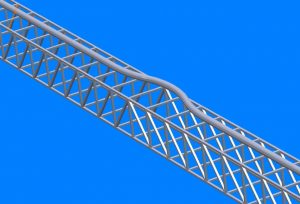

There are a variety of ways to secure a wire rope at the top of a building. One frequently used method in temporary situations is the cantilever beam. The basic concept here is to take a long “stick”, rest it on the roof of the building and stick it out far enough so the wire rope can hang vertically. If the building face is straight, the cantilever is small, not more than a couple of feet. However, if the building steps in (or out), the suspension rope must be positioned further away from the edge of the roof, and, in some cases this could be ten feet or more. The bigger the cantilever, the bigger the stick has to be; the bigger the load, the bigger the stick has to be. Of course, in addition to the fact that the stick has to be the right size, the roof has to support the loads the stick exerts on it.

The roof, or whatever is holding the stick, sees two loads. One load, at the edge of the building, is pushing down on the roof. The other end of the stick wants to lift up. Therefore, the roof has to restrain the uplift force. If the stick is attached directly to the roof with, say a big bolt, the roof has to restrain the uplift load. If, on the other end, a counterweight is used to hold down the rear end of the stick, then the roof has to hold up the weight of the stick and the counterweight.

What is a scaffolder to do? Well, one thing is to make sure the stick is big enough. Another is to make sure the roof is strong enough. And finally, if you are using counterweights, make sure you have enough. Fortunately, the SIA has the answer for the number of counterweights that are needed. It takes into account the length of the cantilever, the length of the stick, the location of the fulcrum (the location of the front support), and the load that is being put on it. Contact the SIA office; they can tell you all about it.

A little more problematic is the stick. We in the profession prefer to call the stick a beam as in outrigger beam or cantilever beam. Choosing the correct size requires an understanding of engineering principles and mechanics of materials. For standard setups, scaffold suppliers have “pre-engineered” beams that address most typical loading circumstances. (How can something be pre-engineered? Either it’s engineered or it isn’t!) The non-standard setup requires a different approach. For those who like more excitement in their lives, a wild guess as to the correct stick may work. For the rest of us who don’t like living on the edge, but don’t mind hanging from it, consultation with a qualified person is recommended. Any situation can be addressed. Just remember, the bigger the cantilever, the bigger the stick and the bigger the counterweight. Building elevators are limited in size and typically don’t go all the way to the top. That means you have to carry the counterweights the rest of the way and somehow you have to get that stick into the elevator.

The roof is the final issue. Most scaffolders estimate the strength of the roof prior to the rigging installation. Read that word estimate to mean guess. Most of the time the guess is good, sometimes it isn’t. Watch out for deterioration of the roof members, additional loads such as ventilating machinery, and other conditions that will affect the ability of the roof to support the rigging. Remember that a 700 pound pile of counterweights can easily overload a roof designed to only support 40 pounds per square foot.

Suspended scaffolds are a beautiful thing, when they work correctly. Make sure the stick is big enough and the counterweights are right. Don’t guess—there are plenty of qualified scaffold suppliers to help you decide which stick is right for your application. As for the roof, I suggest you don’t accept any responsibility for its strength unless you really do know how strong it is. Suspended scaffold rigging is not guesswork!